Form Follows Fantasy

Les Espaces d’Abraxas

Form Follows Fantasy

To mark the Journées nationales de l'Architecture 2024, one of the studios at Les Espaces d’Abraxas opened its doors to the public for the first time, presenting a selection of original documents from the Taller’s archives alongside material from the local municipality. On view were drawings, photographs, film clips, advertising posters, sales brochures, and personal memorabilia, tracing the inception of the project in the 1970s through to its prominent status in pop culture – with appearances in places such as Brazil (1985) and The Hunger Games (2015). The exhibition was accompanied by the following text, exploring the broader social and political forces shaping French society when Abraxas came to life.

Who can truly claim to live in a palace? Few, beyond monarchs, royal families, their ever-present staff, and the occasional member of an ultra-wealthy elite with enough fortune and influence to buy a title (or at least the appearance of one). What of a theatre? Those who spend their lives upon its stage – actors, dancers, comedians – might call it a second home, but they don’t reside in the theatre in any conventional sense. As for a triumphal arch, surely no one could claim to live there. It’s a monument, not a home, a declaration of victory over an enemy or a commemoration of a battle long past.

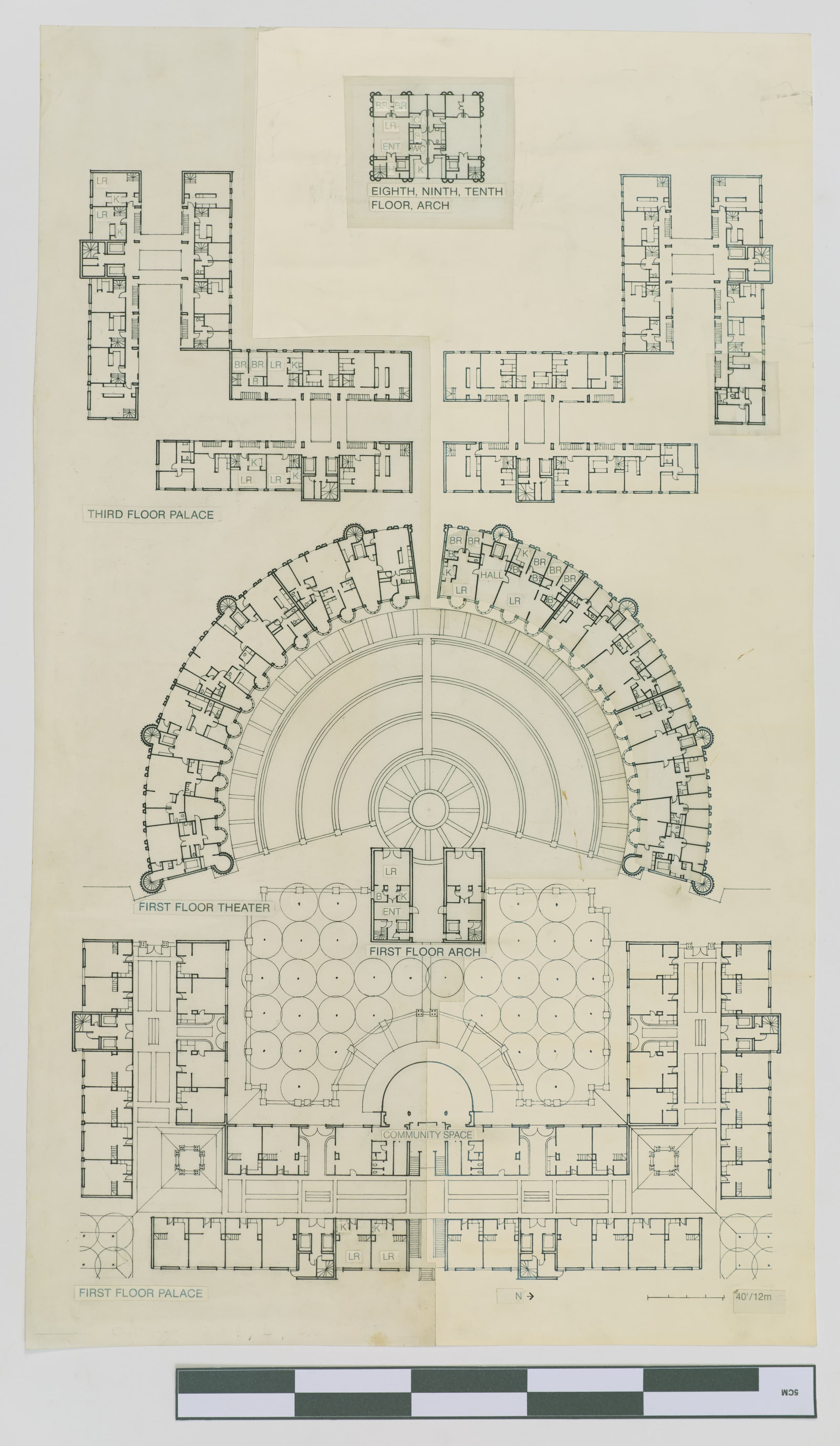

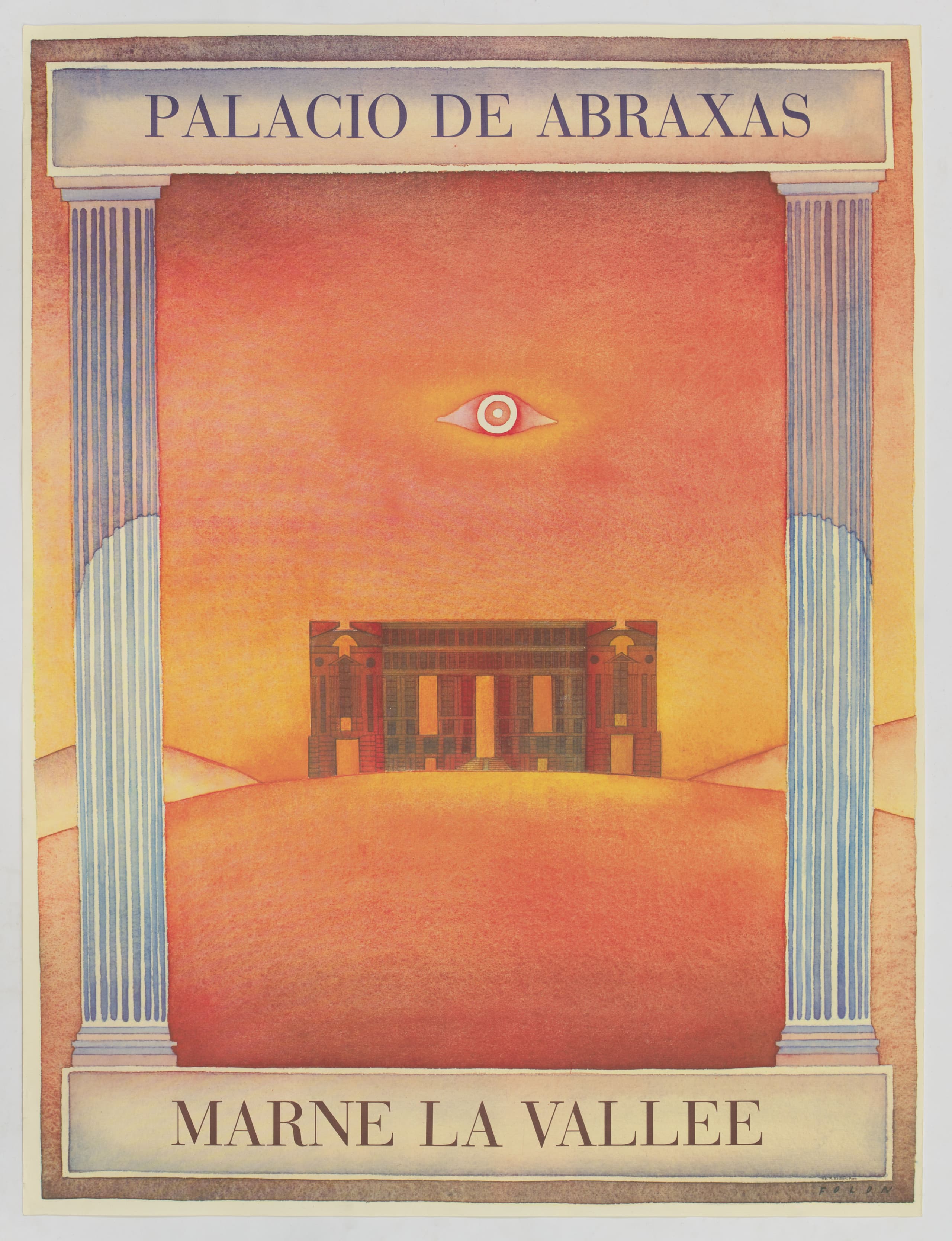

If you’re familiar with Les Espaces d’Abraxas(1) – or simply “Abraxas” as it’s often called – you’ll understand why I pose these scenarios. The estate's thousands of residents can all genuinely say they live in either a palace, a theatre, or a triumphal arch, because the apartment blocks are named and shaped in the image of these classical architectural forms: Le Palais, Le Théâtre, and L'Arc de Triomphe.

A housing complex in Noisy-le-Grand, Marne-la-Vallée, comprising close to 600 apartments over three buildings.

While the idea of buildings that look like other buildings – or like animals (Calatrava), spacecraft (Hadid), or food (half of Las Vegas), for that matter – may seem perfectly ordinary today, it was radical at the time Abraxas was constructed in Marne-la-Vallée. Up until that point, which was the early 1980s, French government-subsidised housing had been trapped in the monotony of a certain sensible functionalism. The “slab block” was default: long grey concrete corridors, identical rows of doors and windows, floors that repeated ad nauseam.

This style – or lack thereof – emerged during the 1920s(2) then gained momentum across the housing sector in the wake of World War II. Cities had been levelled by bombs, leaving millions of people displaced, pushed from urban centres and into their expanding suburbs. In-situ concrete was the quickest, cheapest, and most efficient way to house such a large number of people, and was thus poured exponentially.

L’Unité d’Habitation (or the Marseillan block, as it's sometimes known) by Le Corbusier is arguably the most influential example of this building. Constructed in 1952, the ship-like monolith synthesised the architect’s research in housing and community living, and would set a precedent that remains pertinent today.

But such functional architecture could often come at the expense of spirit. “Form follows function”,(4) the guiding mantra of the Modern Movement, had dictated that a building’s design should be subservient to the activities it housed. Fine. But this was taken to mean that ornament, colour, joy – frankly anything that might be considered unnecessary or extraneous – was to be vehemently avoided(5) , too. As history goes, the foundational charter was muddied and simplified, and the triumph of many early Modern buildings was nowhere to be seen in the later landscape of bare efficiency, with its buildings stripped of character and individuality.

A maxim coined in 1896 by the rationalist architect Louis Sullivan, reportedly inspired by rationalist thinkers of the moment as well as the Vitruvian idea that a building should be solid, useful, and beautiful.

Adolf Loos went so far as to suggest that decorating buildings deserved institutional punishment with his 1910 lecture titled: ‘Ornament and Crime’; an essential study for architects following the movement.

And so, by the mid-1960s in Paris, the housing crisis had morphed into something more profound. This was now an architectural crisis, a search for the very soul of the city, on top of what was an already desperate need for simple shelter. Sensing the situation was inching towards total collapse, the then-president Charles de Gaulle assembled a team of the greatest urbanists, engineers, architects, and planners in France. These people were set a task: create new towns around the capital city to absorb the suburban sprawl(6) , and do so through architecture not just functional, but humane, even beautiful.

The plan for the new towns can be condensed into four primary goals: to restructure the suburbs, reduce commute time, provide jobs and services, and serve as a laboratory for urban planning.

To find answers, the team needed first to escape the grip of France’s architectural establishment, then dominated by a few “dignitaries from the Modern Movement” and the esteemed École des Beaux-Arts.(7) The team turned its gaze south, across the Spanish border to Barcelona where Ricardo Bofill and his architecture workshop were making waves with their unconventional, near utopian social housing projects.(8)

Dominique Serrell’s recent publication, Ricardo Bofill: The French Years, charts in detail the astronomic rise of Ricardo Bofill and his Taller de Arquitectura across France, set in motion by the new town mission (read on).

The Taller de Arquitectura (Architecture Workshop) was founded in 1963 by a young group of unorthodox thinkers – among them a poet, a mathematician, a critic, and an actor. Their vision for an egalitarian society, built on shared principles manifested in public space, continue to inform the Taller's work today.

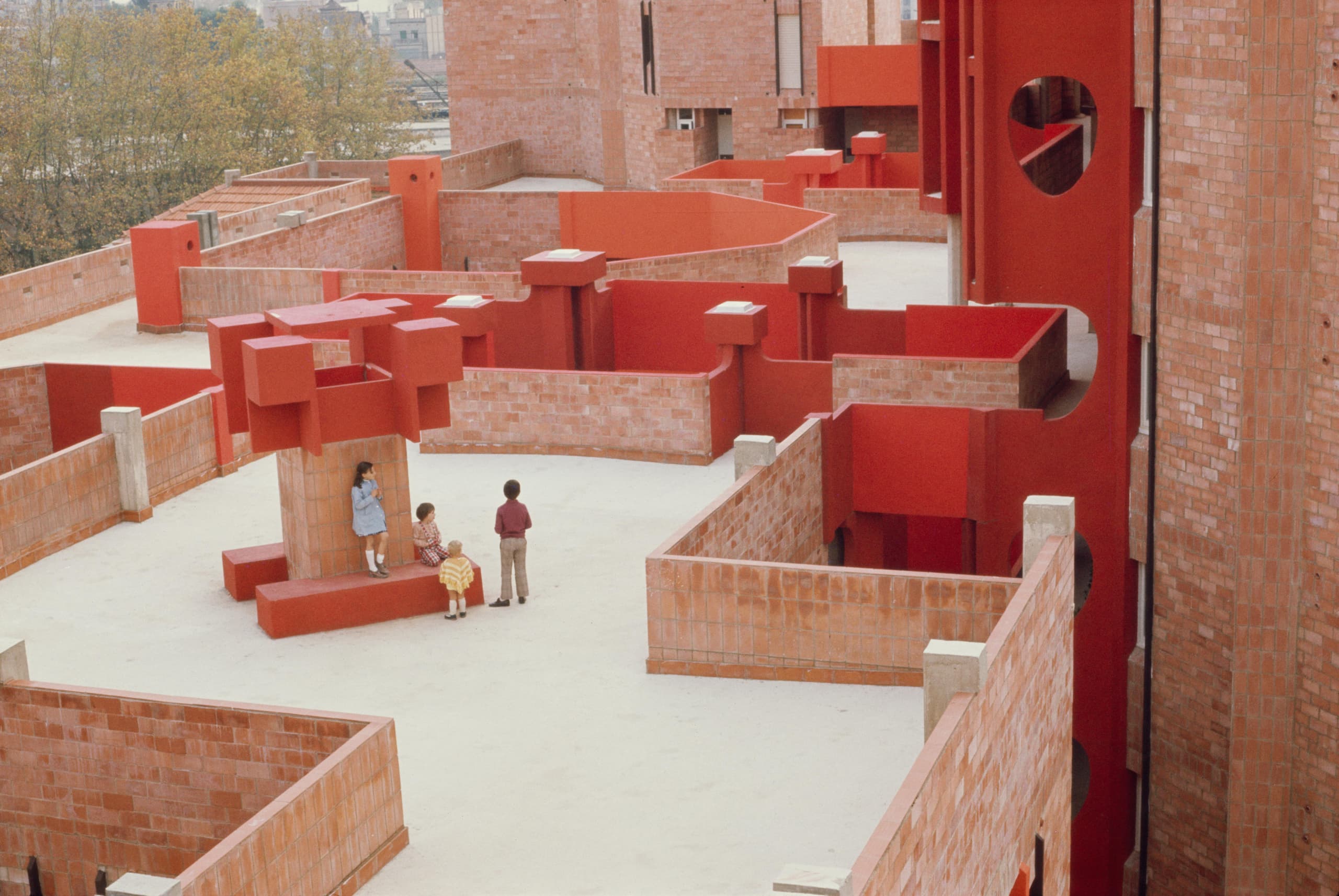

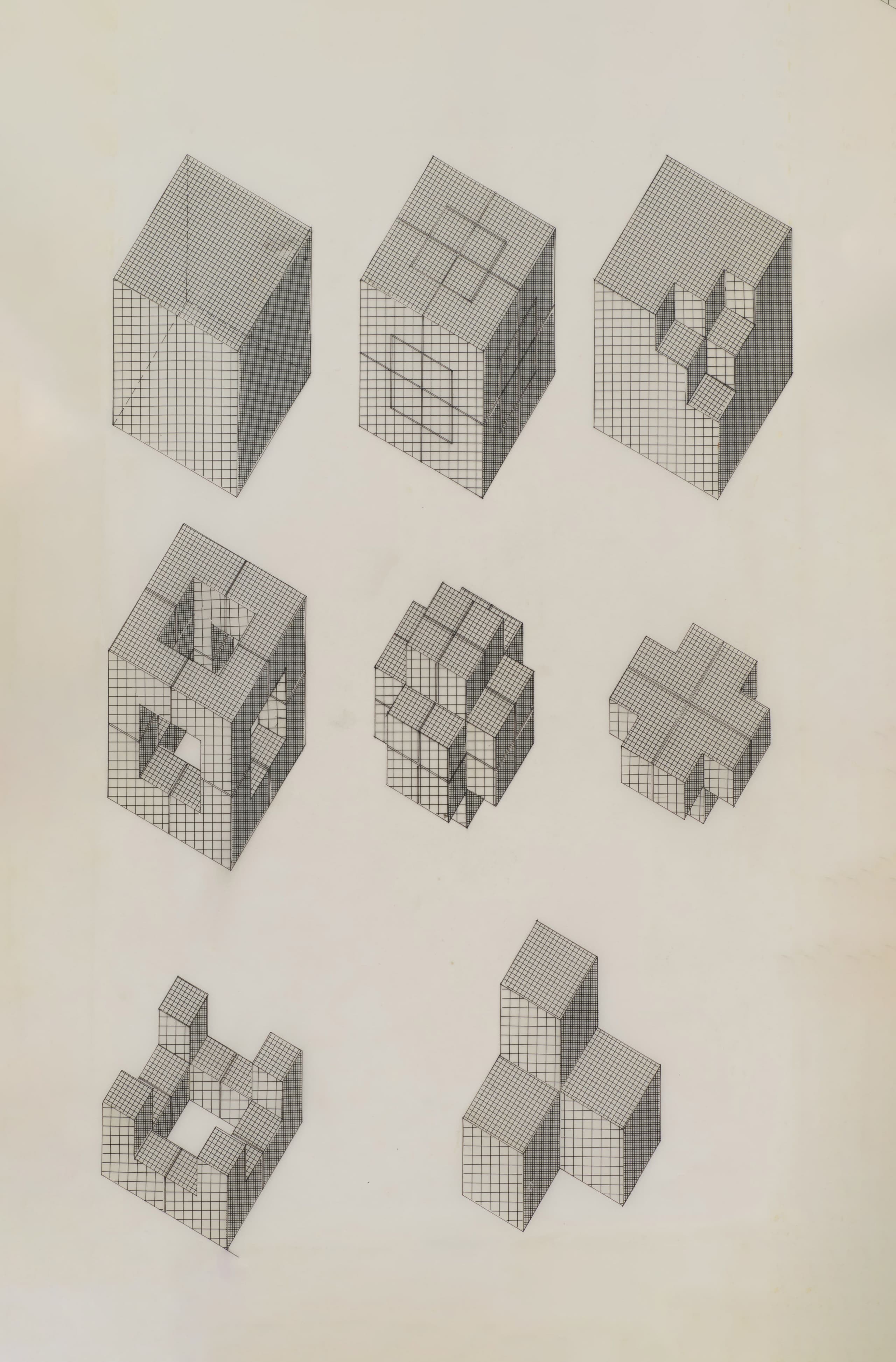

These were buildings that defied normal housing standards: there were less apartments, more complex modulated structures resembling honeycombs, termite mounds, or the ancient warren of a forgotten city. They broke from the monotonous block and sought to revive the communal spirit and customs of Spain, with places to meet and converse, to stroll, to sit in the sun or argue – spaces designed for life, not mere survival. In projects like Walden 7 and Barrio Gaudí,(9) these traditional qualities mingled with surrealist and futurist imagery, offering proposals for an entirely new way of living, one that looked backwards and forwards in equal measure.

Both adopt the name of an inspiration to the Taller: the former, from a literary series of utopias written by Henry David Thoreau (the original Walden) and W. B. Skinner (Waldens 2 through 6); the latter, from the creator of Catalan Art Nouveau.

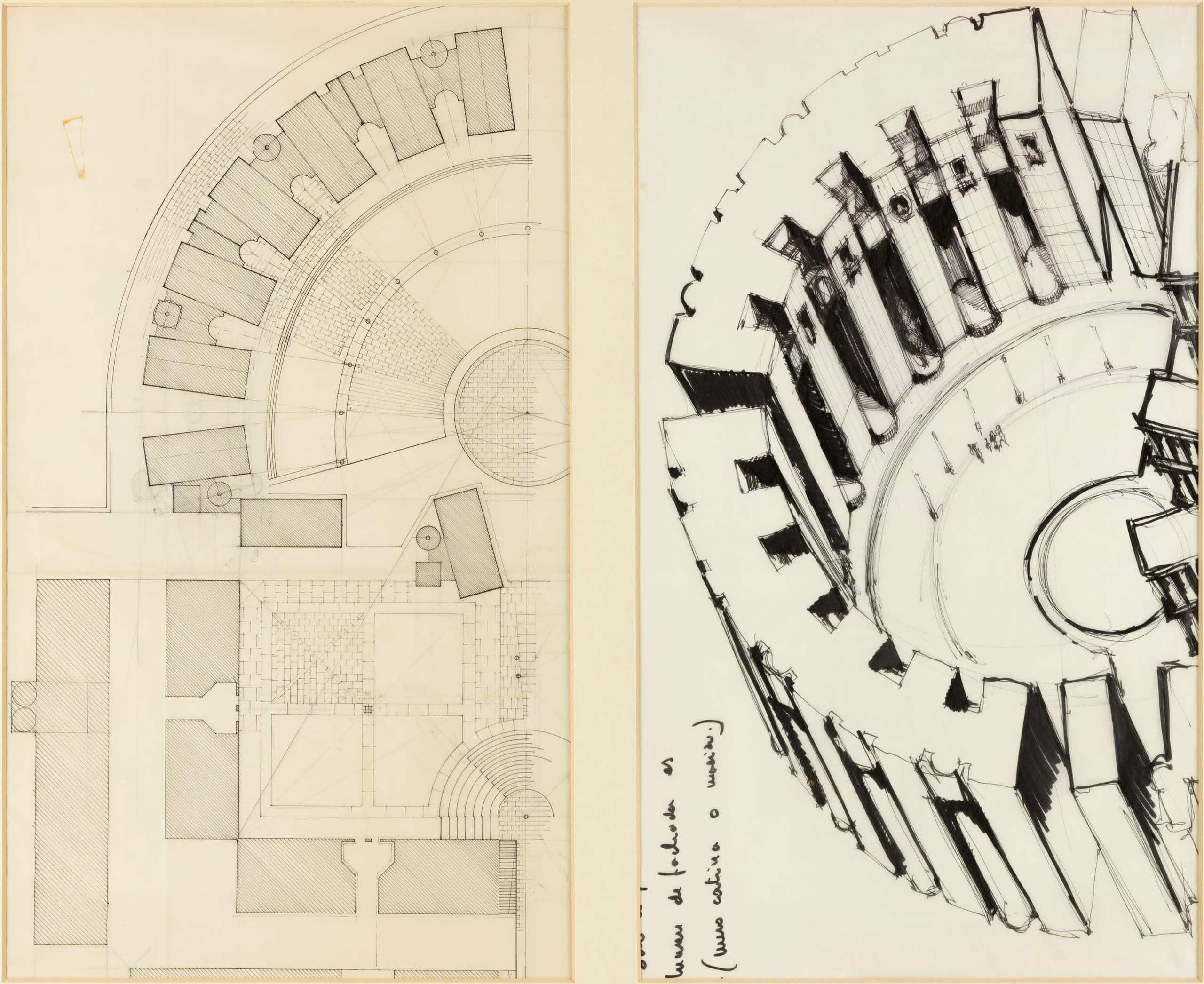

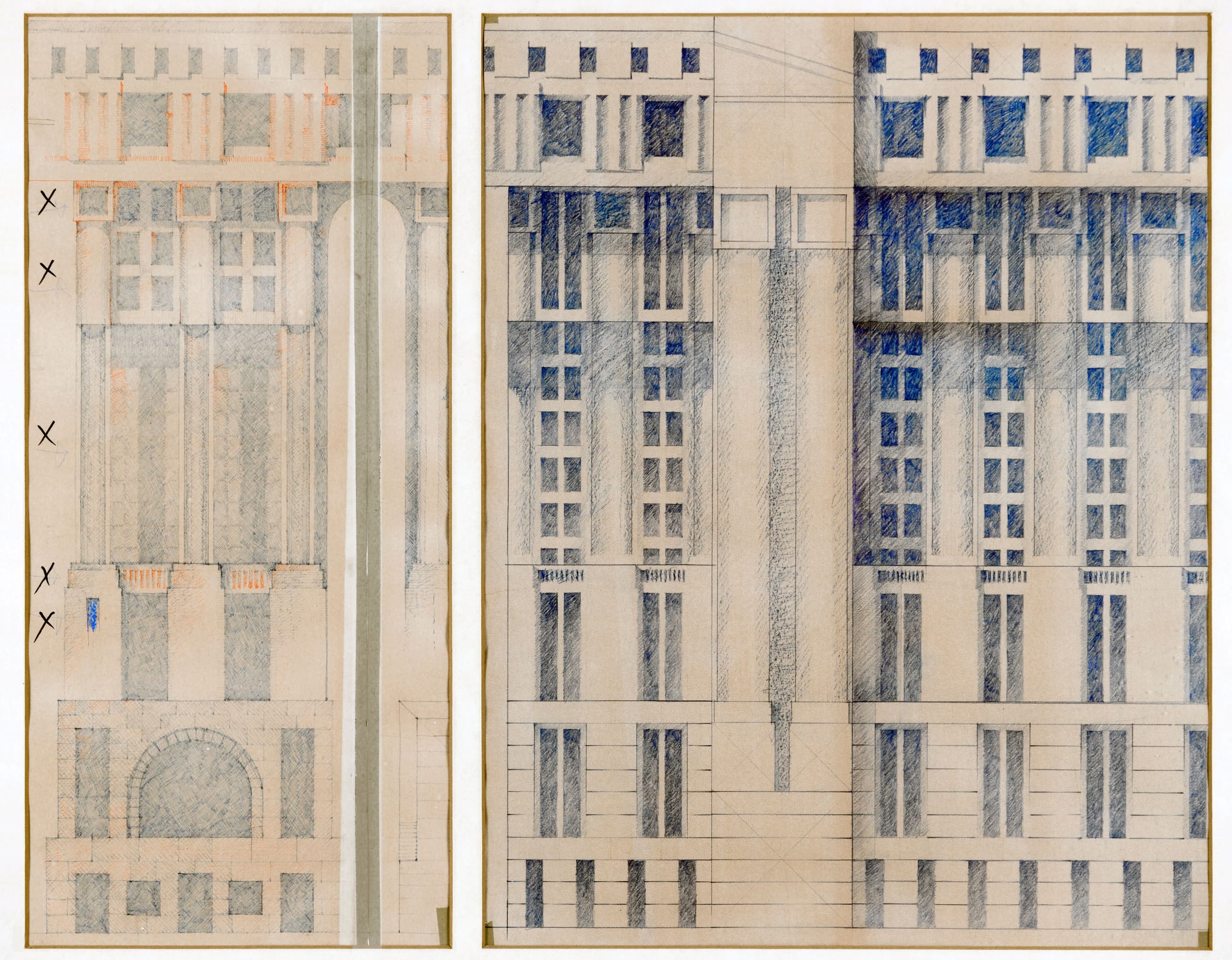

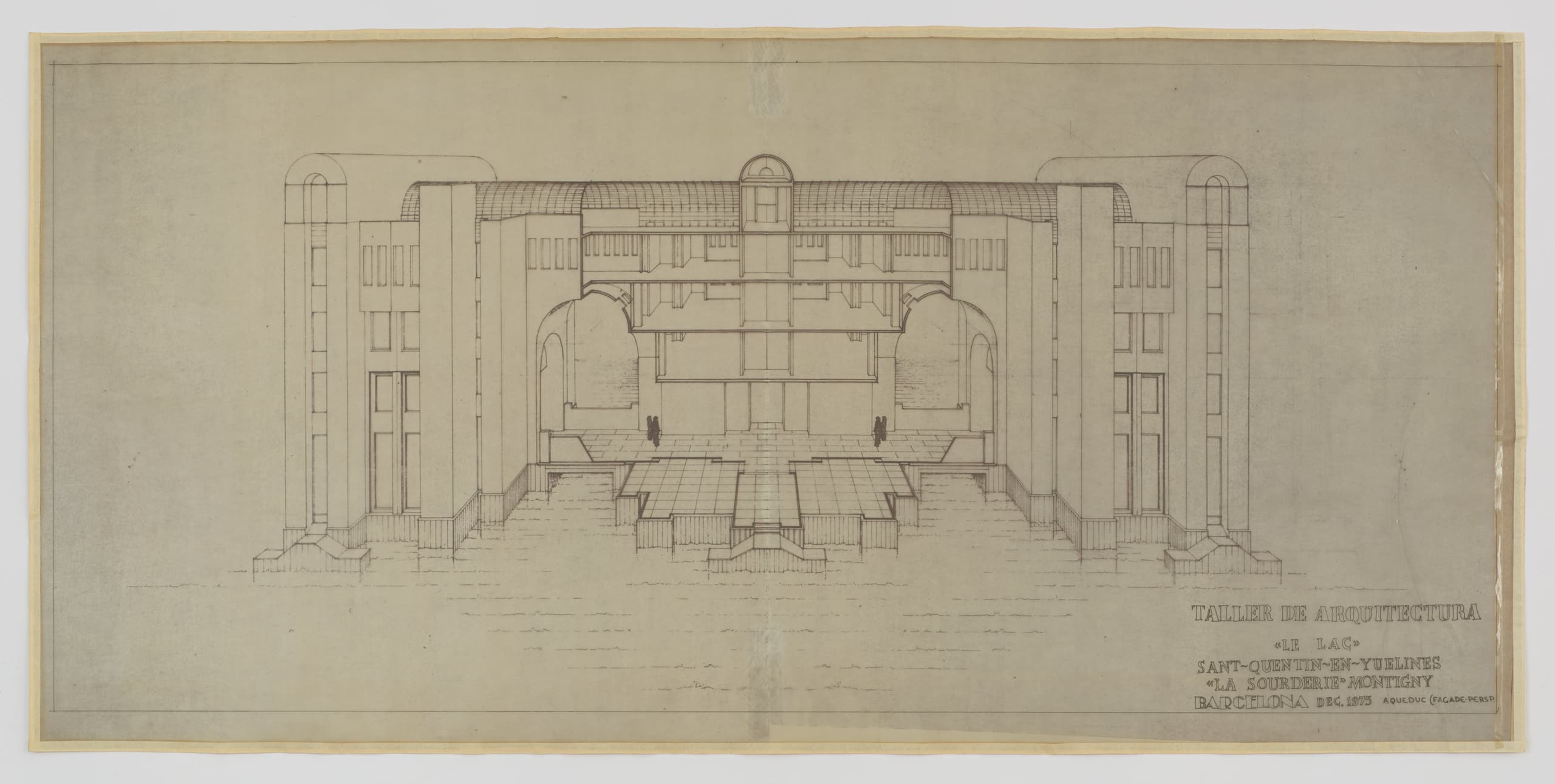

The Taller’s vision seemed to align effortlessly with that of the French, earning the architects the commission for social housing projects in two of the five proposed new towns.(10) One of these sites was located in Marne-la-Vallée, ten kilometres outside of Paris. Its brief called for a “monument-project” to give the new neighbourhood an architectural identity, or “a symbol that was both striking and representative.”(11) The Taller's initial designs were developed from the cubist concepts that had generated La Ciudad en el Espacio, with facades inspired by another very different project, Les Arcades du Lac, creating a grand gesture that would cut across the landscape. The overall composition took its cues from the orderly axes of boulevards, formal gardens, and the nearby grandeur of Versailles to create an architecture other than that for which the Taller was recognised.

The first was to be located in Cergy-Pontoise but was ill-fated; an instrumental conservative governor refusing to sign off on such an avant-garde, progressive vision for social housing meant the “Petite Cathédrale” never came to fruition.

Remembered by Ricardo Bofill in an archive text written on the occasion of the project’s completion in 1983.

This was a shift towards contextualism – or “city-based morphology” – which could be felt well outside the grounds of La Fábrica. It marked a generational change, later dubbed “Postmodernism”, the catch-all term for various reactions to the failures of Modern architecture: its inability to generate compelling public space, its breakdown in communication, and, perhaps most pointedly, its loss of meaning. This new movement would gather around a “richer language” based on metaphor, historical imagery, and wit, suggesting that classical architectural vocabulary could be perverted or subverted, and that its qualities extended far beyond traditional archetypes.(12)

Extracted from ‘Post-Modern Architecture’, a text written by the critic who coined the name of the movement, Charles Jencks, published in the 1979 edition of Environmental Communications catalogue.

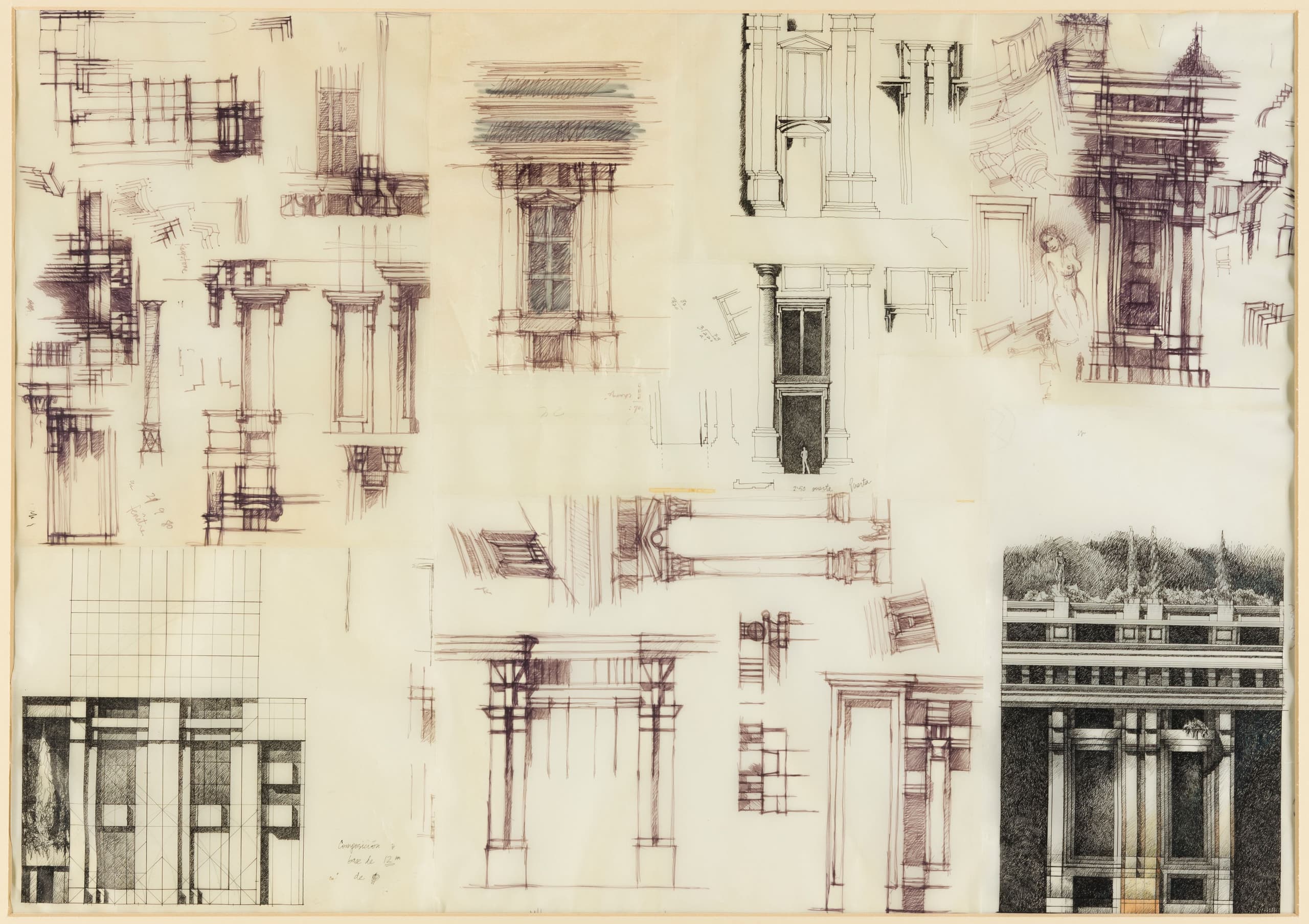

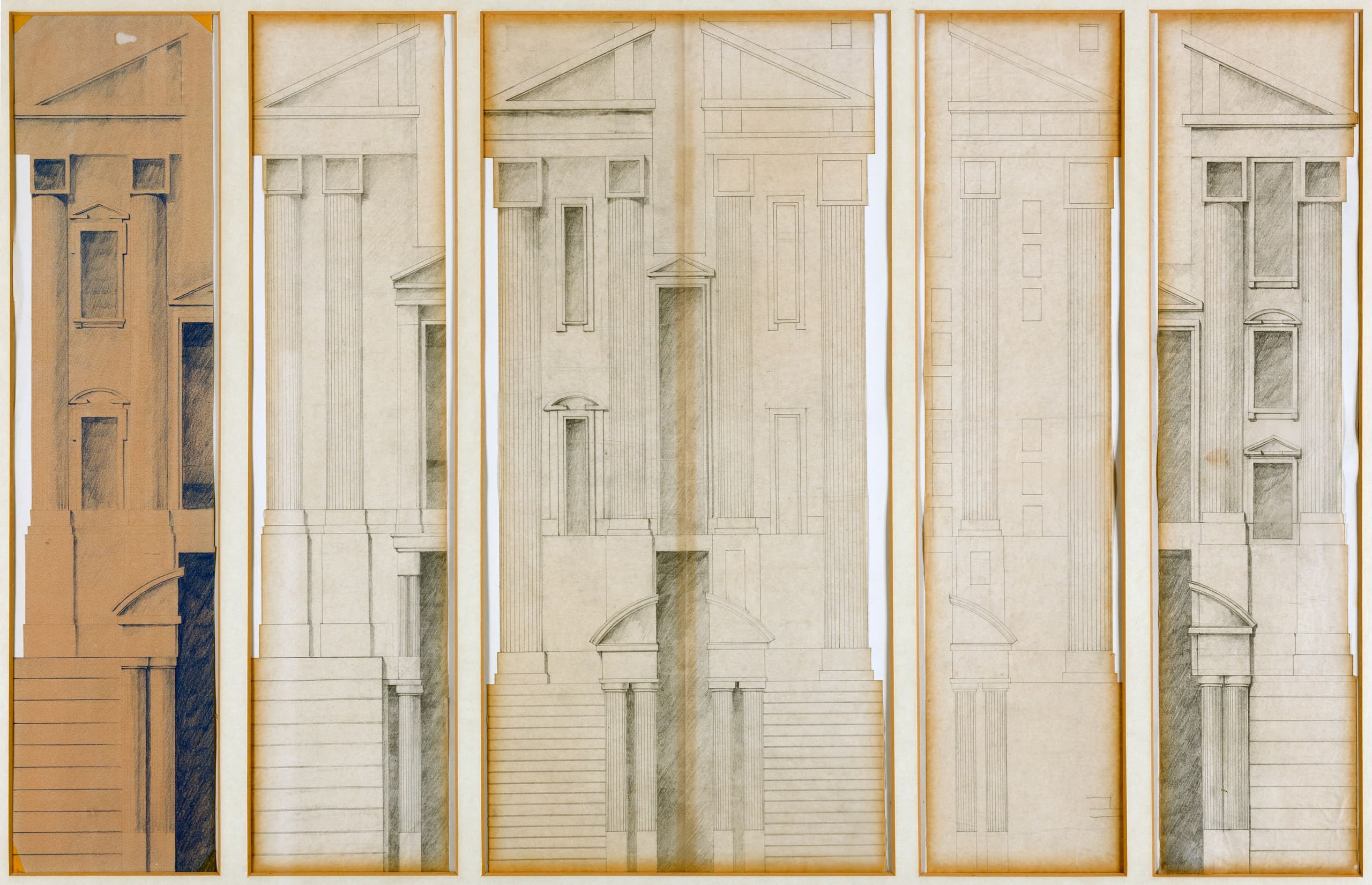

Fuelled by this international change in appetite, the Taller adopted a fresh approach and issued a second round of plans for Marne-la-Vallée.(13) Now that function no longer appeared to bind form, the apartment units could be poured freely into the shells of those three classical building typologies: the palace, the theatre, and the triumphal arch. The employment of these distinct archetypes intended to impart their dramatic spatial qualities on affordable dwellings, hopefully providing residents with a heightened sense of living. Meanwhile, the cubism that had defined the Taller’s earlier work made way for a playful collage of Greek, Roman, and Baroque motifs, where colossal Doric columns became fire-escape stairwells and cypress trees adorned the facades like classical friezes.(14)

This happened around the same time the Taller participated in the first ever Venice Architecture Biennale, The Presence of the Past (1980), which put Post-Modernism at the centre of architectural discourse.

The Doric is the "strongest" of the five orders; classical styles of architecture based on proportion and decoration. Its masculine appearance made it suitable for structures related to nobility and soldiery in ancient Greece and Rome.

Construction of such an acropolis would be no small feat – plus the Taller was working with a modest budget to keep apartment prices subsidised. The (neo-)neoclassical vocabulary had to therefore be adapted to an industrialised building system, something that only a concrete factory outside Lyon, originally developed for nuclear power plants, could master. Over the course of two years, prefabricated facade panels with unrecognisably faux finishes of marble and limestone were prototyped and perfected by this factory using oxide colouring, relief work – the whole works. These panels were then transported to the site by lorry and hoisted into place by tower cranes,(15) a technical spectacle right before the eyes of the new town's new residents.

Jonathan Meades detailed the construction method in an issue of popular English magazine Time Out (January 1981), directing readers to an exhibition of the Taller’s work running at the Architectural Association in London at the time. The feature was titled: ‘The Don Quixotes of the New Classicism’.

As Le Palais, Le Théâtre, and L'Arc de Triomphe rose above the surrounding motorways, subways, car parks, and office blocks, the buildings earned titles including Edifices for Everyman and Palatial Pleasures for Urban Masses.(16) Read as a whole, their actual name was "Abraxas", a word that carries a rich depth of meaning: Abraxas is an ancient charm constructed from Greek letters; it also represents a supreme Gnostic deity, ruler of the 365 circles of creation, one for each day of the year.(17)

Given by Peter Lemos in ‘A Classical Act’, an article published in the Pan Am Clipper (May 1989), the American airline’s in-flight magazine. Similar reviews were written for niche to regional and international newspapers and magazines; Ricardo Bofill and the apartments in Marne-la-Vallée had achieved celebrity status.

A source of great mysticism, Abraxas is a sequence of Greek letters thought to possess special qualities; the number 365 corresponds to the numerical value of its seven letters. It was personified as a god by Gnostic teachers in the 2nd century AD.

Embedded within this latter definition is the idea that each day is a miniature cycle of life and death. Naming a housing estate as such might seem like an extreme position to take – especially when the more common lived experience during the 1980s (a behemoth of a decade in neoliberal terms) was one of nine-to-fives, much the same, Groundhog Day.

The Taller knew this. With Les Espaces d’Abraxas, the group was suggesting something else entirely, offering an invitation to residents – and to tired architectural rhetoric alike – to “break free from the mediocrity of the everyday”.(18) It was through grandiosity, theatrics, and occasion that the Taller sought to reinvigorate the mundane architecture of mass housing. Arguably, the group succeeded.

Something Ricardo Bofill ‘always believed very strongly’ – from a text written in 1983 on the occasion of the project’s completion.