Il Giardinetto X El Taller:

50th Anniversary

La Ciudad en el Espacio

LOCATION

Madrid

CLIENT

Ministerio de la Vivienda de España

YEAR

1971

STATUS

Completed

TEAM MEMBERS

Emilio Bofill, Ricardo Bofill Levi, Peter Hodgkinson, Manolo Nuñez Yanowsky, Xavier Bagué, Ramon Collado, Anna Bofill

SEE CREDITS

OVERVIEW

LOCATION

Madrid

CLIENT

Ministerio de la Vivienda de España

YEAR

1971

STATUS

Completed

For much of the 1960s, the research objective at the Taller was a new approach to urban housing. There was a need for low-cost, good-quality, high-density apartments in Spanish cities where, as in the many nations affected by war earlier that century, housing systems had been decimated by crumbling socioeconomic standards as well as actual concrete destruction. One (if not the single) positive outcome of this turmoil was a widespread sense of unrestrained possibility – a clean slate – that would allow all sorts of utopian, often communitarian visions for the future to emerge.

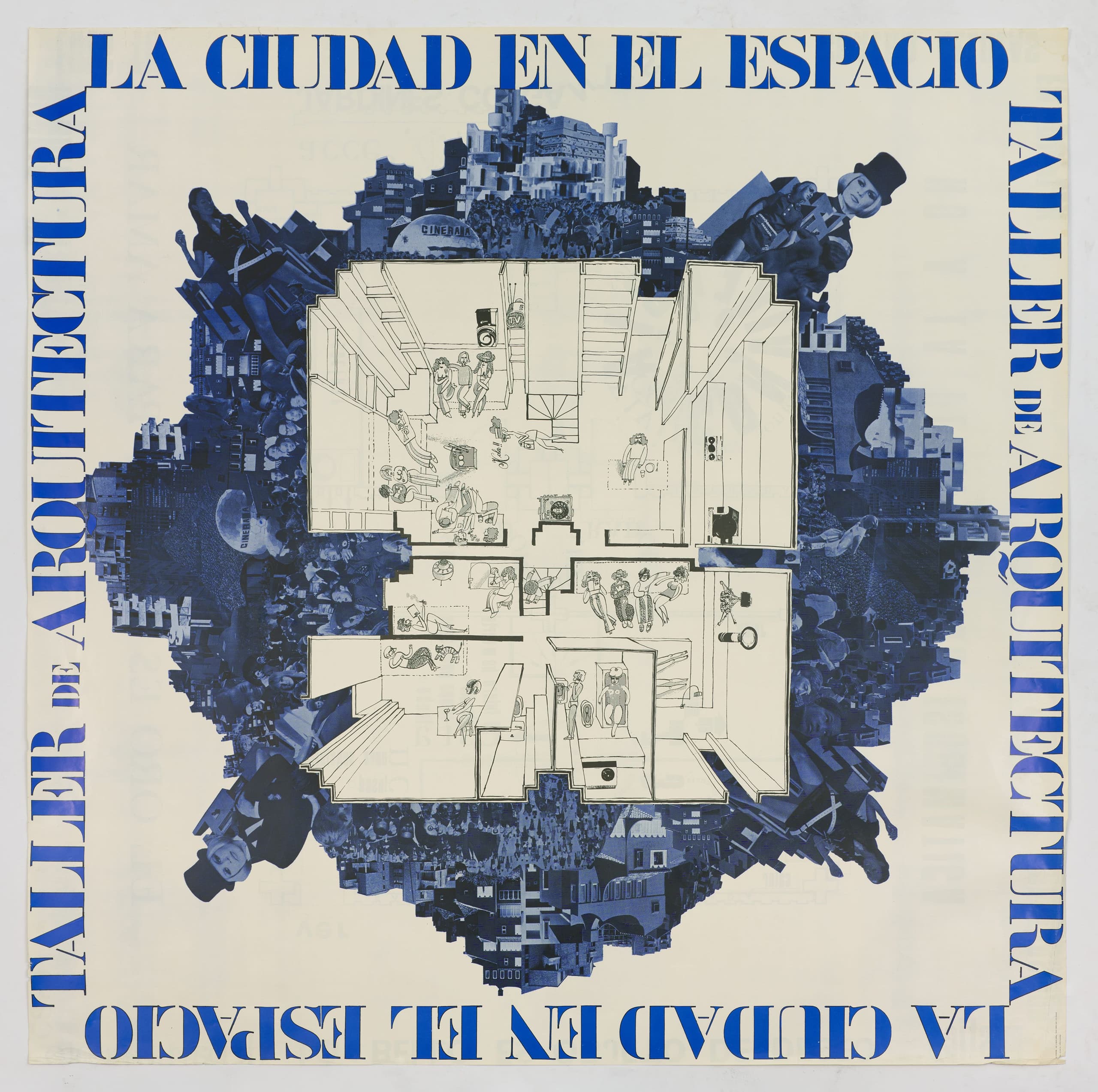

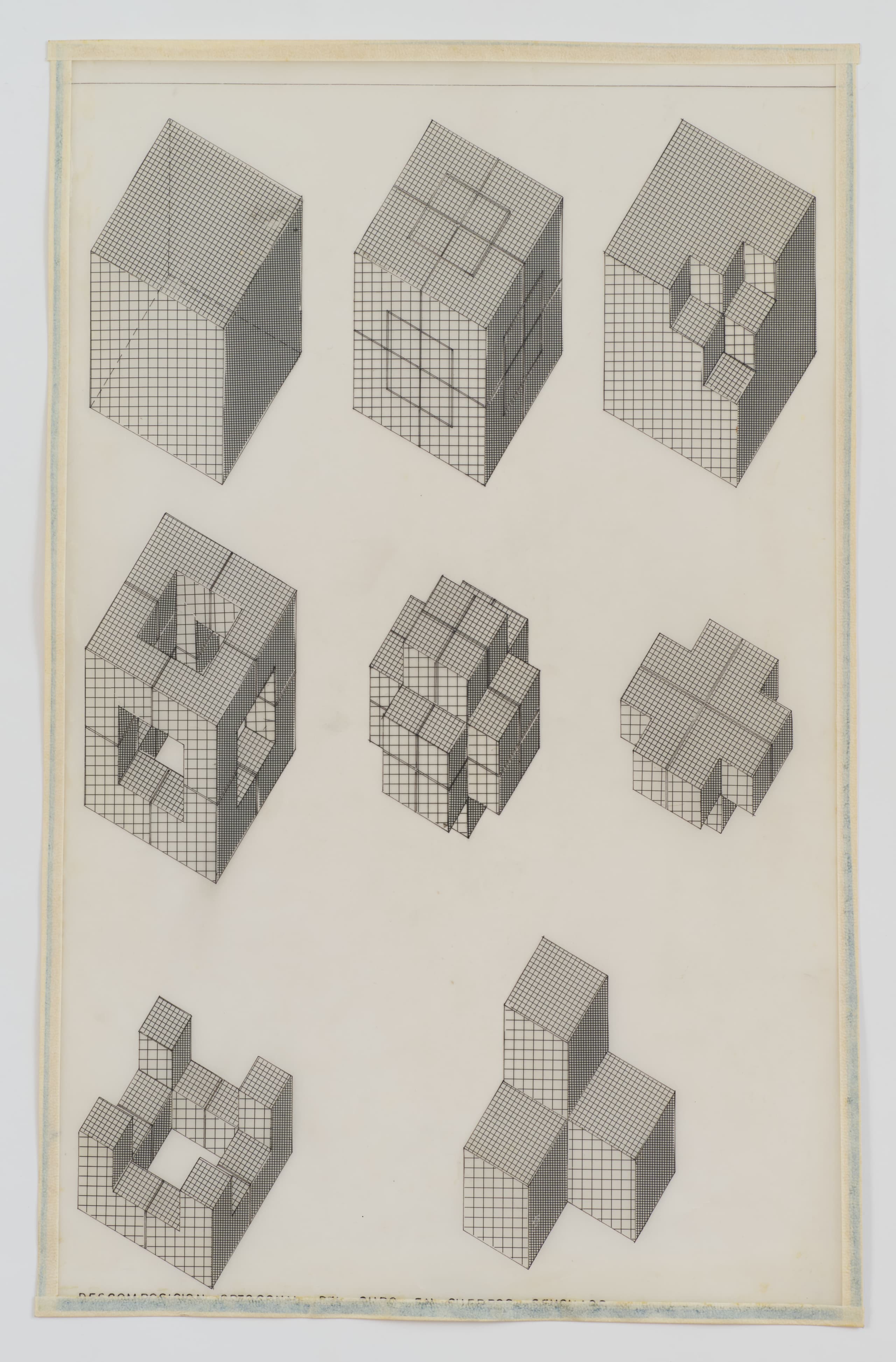

The Taller published its vision in 1968 with the manifesto Hacia una formalización de la ciudad en el espacio (Towards a formalisation of the city in space), putting into words and building upon the methodology behind projects Barrio Gaudí (then under construction) and Xanadú at La Manzanera (constructed). “Methodology” basically described the ways of working with cubic volumes to form large city-like structures, using elementary building materials and processes while reproducing traditional qualities found in Mediterranean towns and villages. Its publication would give rise to further projects or “Experiences”, first in Madrid and later in Barcelona.

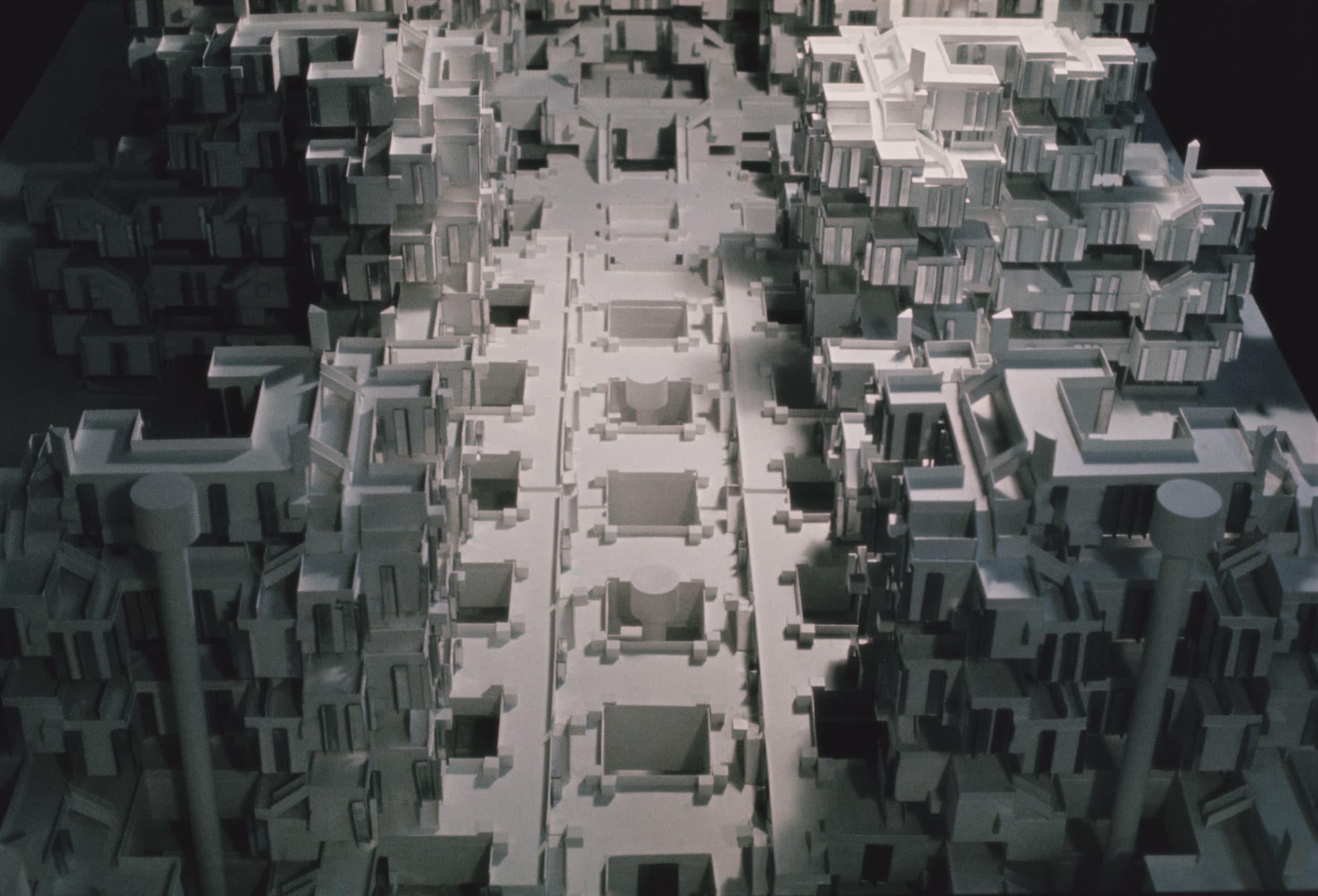

Experience 1 proposed 1064 dwellings for a 114,700 square metre plot in Moratalaz, Madrid. The idea was for apartments to be composed of multiples of one basic module to produce a range of sizes, from studios to 6-beds, which wrap around a central core containing the services and circulation. Extending over a cubic grid, the clusters of modules grow upwards and outwards, forming terraces on the roofs below for either private outdoor space or as part of a planted public walkaround. The result is a city garden in space, with labyrinthian passageways and changing sightlines through holes in the constructed mass, as well as apartments with sunshine, fresh air, and their own gardens and views.

To construct the modules, a simple phased system was devised: three pieces of concrete on a steel node which adapt to any orthogonal permutation. The diagonal (ramps and stairs) require an extra harness, and any cantilever designed into the structure uses a steel strut. The concrete pieces are waffle slabs shuttered with reusable steel, solidified with poured concrete, and infilled with a material called Ytong. This infill can be sawn to shape soft corners and built-in handrails, and also acts as an excellent thermal barrier.

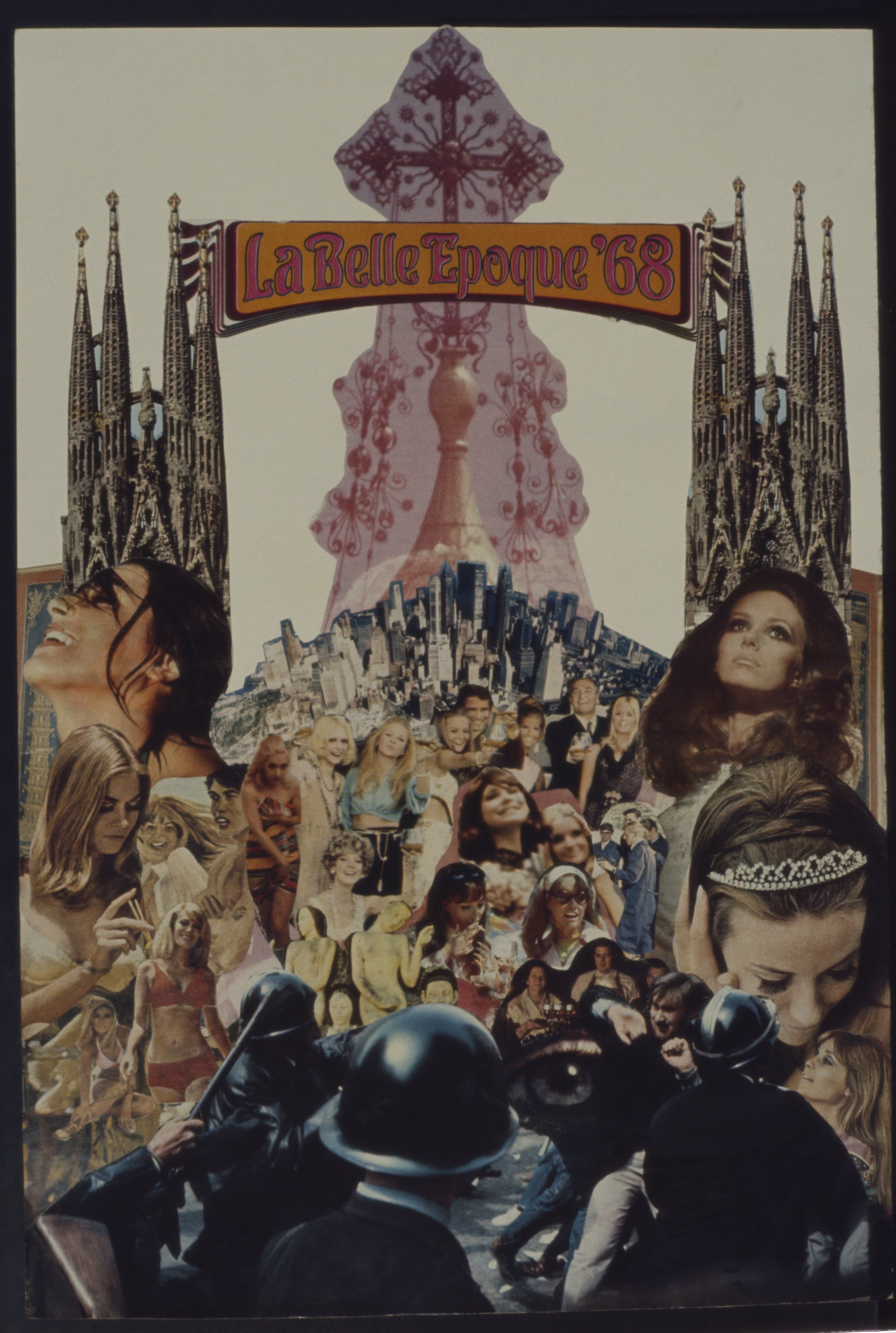

The homogeneous structure was to be placed over irregular terrain, generating pockets of open space at ground floor for automotive access and public provisions: shops, workshops, recreation grounds, a church, and a school; altogether a multifunctional neighbourhood, similar to the kasbahs and historic old towns the Taller had studied. The group also saw their thinking represented in Henri Lefebre’s 1968 book Le droit à la ville (The right to the city), which demands that inhabitants have the power to participate in the production and transformation of the urban environment. In this spirit, once the design was finalised, a series of events were staged to engage the public in the City in Space through various forms of artistic expression: music, theatre, performance, and ephemeral architecture.

First was an exhibition presenting large models and drawings of the project in the Feria del Campo de Madrid; second, an open-house at the project headquarters, where mimes and actors produced shows and short films (including Circles: the Five Faces of the Cube); and third, the construction of a grand stage on the site itself for a week-long festival. Though they were attended by thousands of people and sparked huge interest in the City in Space, the events ultimately led to the blocking of the project by Madrid’s right-wing government for nerves surrounding its radical potential. The Taller pursued their theory nevertheless, constructing Walden 7 soon after and carrying many of its ideas through to projects today.

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA