The idea that a cement factory might one day be transformed into an architecture studio and family home would have seemed improbable if not absurd just half a century ago. Typically, buildings were either demolished and replaced or simply abandoned once they no longer served their original purpose. Industrial structures in particular were built incrementally, evolving in response to changing production needs, then left to decay as technological advancements rendered them obsolete. In Spain, the end for much of the industrial sector came in 1973, triggered by the oil crisis and followed by ‘reconversión industrial’, a far-reaching effort of technological modernisation.

It was in the midst of this upheaval that Ricardo Bofill, driving westward out of Barcelona one afternoon, happened upon an abandoned cement factory: 31,000 square metres of soot-streaked concrete, complete with thirty silos, a towering chimney, four kilometres of underground tunnels, and a maze of rooms filled with heavy machinery – all set for demolition within the month. Bofill, recognising the factory’s potential, struck a deal with its owners and acquired the lot. Members of the Taller de Arquitectura promptly moved in, setting up makeshift living quarters among the ruins as they began reimagining the site.

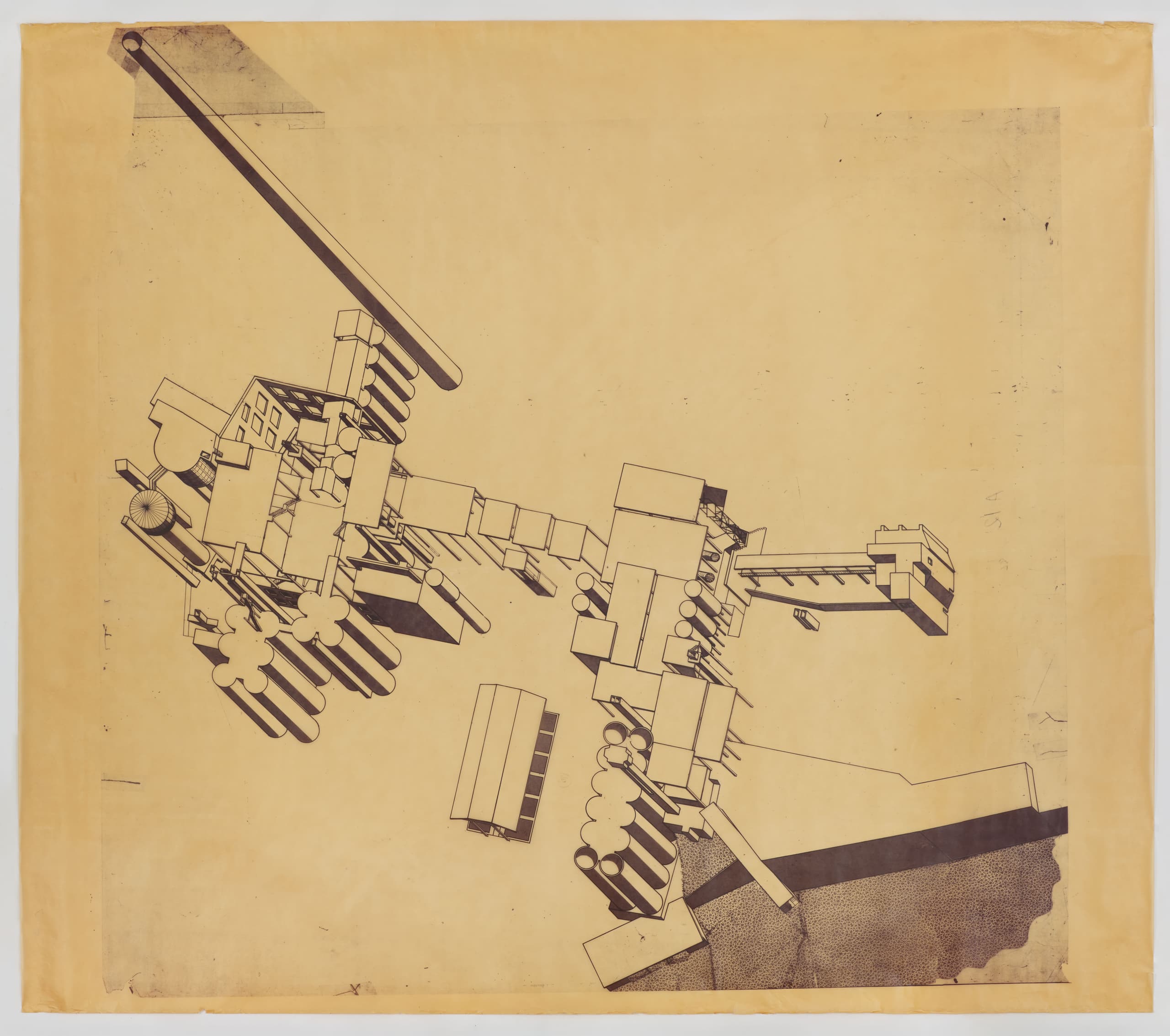

Next door, construction got underway on Walden 7, a vertiginous hive of modular apartments designed by the Taller. Sales from that development would help fund the factory’s reinvention, which paradoxically began with an act of creation-by-destruction. Black-and-white photos were marked up in fluorescent colour; sections of the factory were obliterated by jackhammers and (at times) dynamite; and the ensuing rubble was cleared over the course of two years. As the debris fell away, a surrealist sculpture emerged: staircases suspended in air, voids behaving like volumes, geometry flouting gravity.

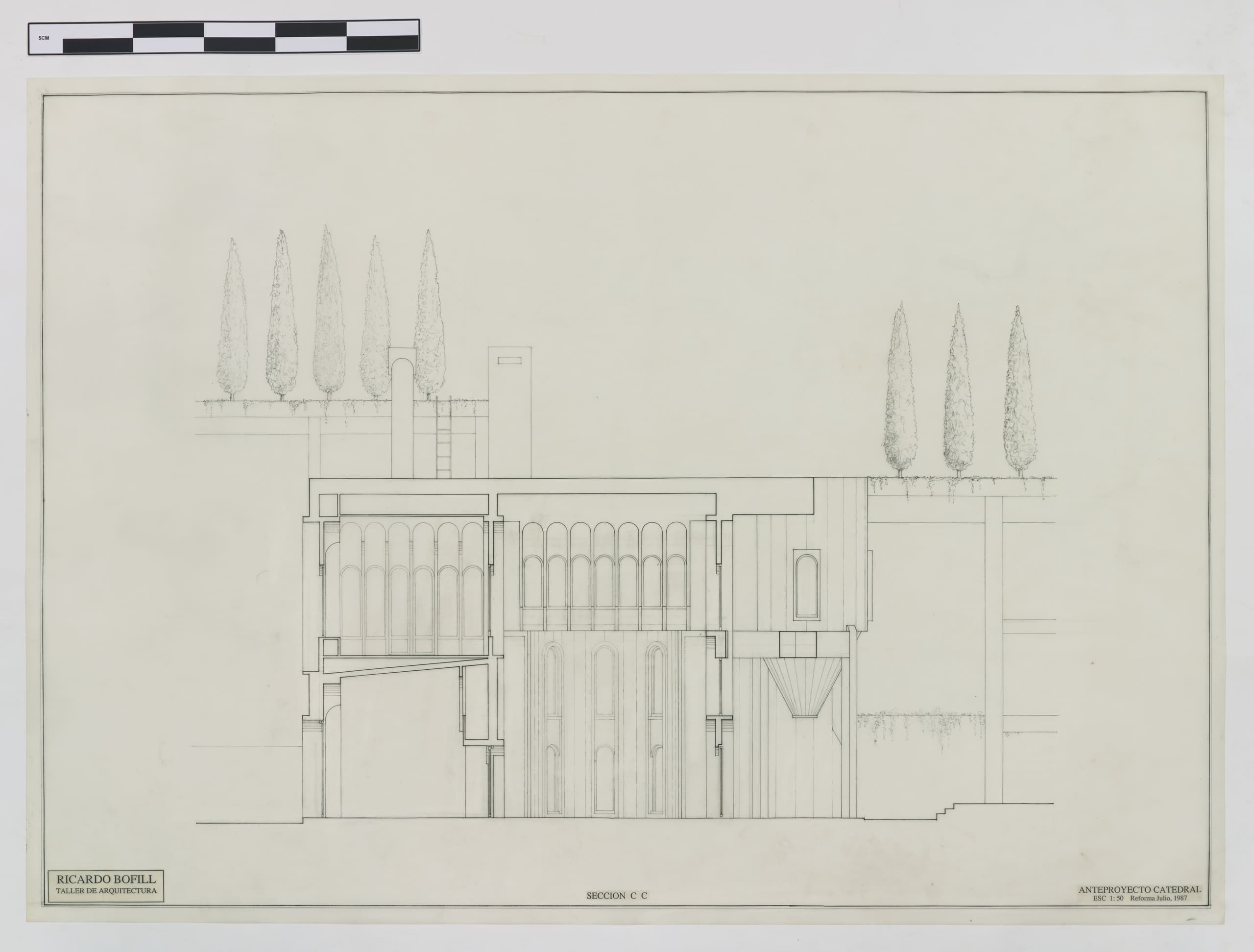

The repurposing of an industrial building on this scale was then unprecedented in Spain, allowing for considerable flexibility in navigating the building regulations. The stripped-back complex was reshaped from the inside out, providing the Taller and the Bofill family with offices, archives, print rooms, model workshops, and accommodation. The heart of the complex – labelled La Catedral, a cavernous hall that contained silos and funnels – was transfigured into the Taller’s central studio.

With grooves bored into the silo walls, floor plates and spiral staircases could be inserted next, transforming each cylinder into a three-storey office. Hundreds of narrow arches – informed by Catalan Modernism – were carved into the raw concrete, opening up windows and doorways to bring some semblance of order to the layout. They also flooded rooms with natural light; La Sala Cúbica, with its access to the roofline and an interplay of various sized arches, is one such light- and air-filled space.

As important as the factory's interior remodelling was that of its landscape. Drawing from Arabic water gardens, Japanese asymmetry, and French formalism, vegetation was planed around and atop the factory in Romantic fashion. Plants such as palms, ferns, vines, olive trees, cypress, and eucalyptus now envelop the building, blurring the boundary between architecture and nature and eliminating the need for traditional facades. In recognition of its innovative design, La Fábrica was awarded the City of Barcelona’s Architecture Prize in 1980.

The adaptive reuse of industrial buildings is now both a prevailing architectural trend and a practical necessity – central to the sector’s response to the climate crisis (by minimising emissions associated with demolition and new construction) and reflective of an increasing sensitivity to place (through the recognition of layered histories, identities, and contexts). At fifty years old, La Fábrica stands as an early and still actively evolving example of this ethos – a testament to human ingenuity and the potential of architecture to act both as subject and agent of transformation.

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA

SALVA LÓPEZ

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA

SALVA LÓPEZ