63rd Salone del Mobile:

Sam Chermayeff Office

Boxes

63rd Salone del Mobile

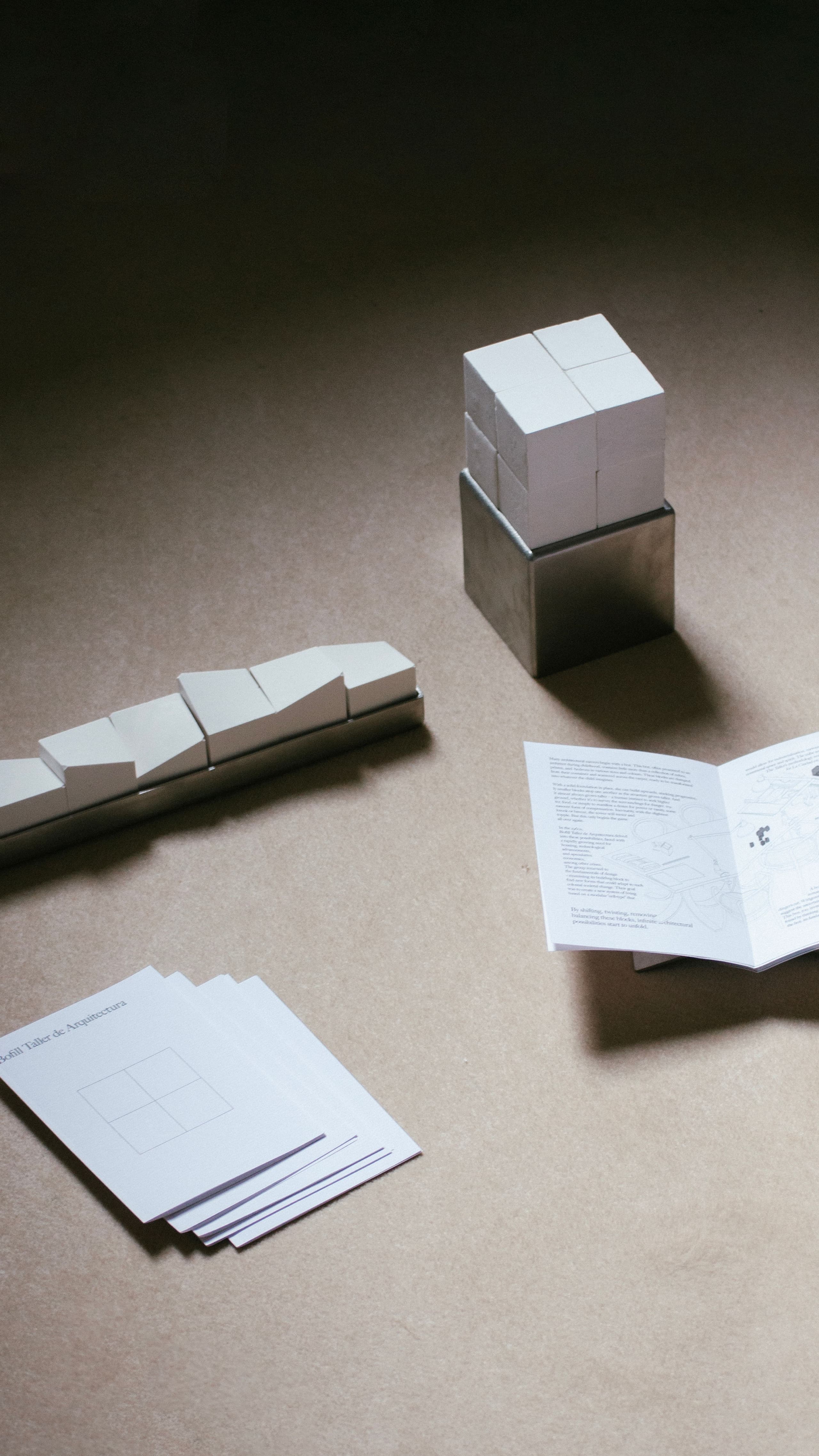

Think outside the box, they say – but what was inside it to begin with? Schrödinger’s cat, Wittgenstein’s beetle, Ursula Le Guin’s carrier bag – they all suggest the unknowability and possibility of what lies within. Who’s to say the contents of this proverbial box are less interesting than the world surrounding it? And what of the box itself? For the 63rd edition of Salone del Mobile, Sam Chermayeff Office asked thirty architecture studios to design, assemble, upgrade, recycle, or acquire a box, sending their contributions to the Dropcity Centre for Architecture and Design. Below is the Taller's response: a replica of a box that has long lived on Ricardo’s desk.

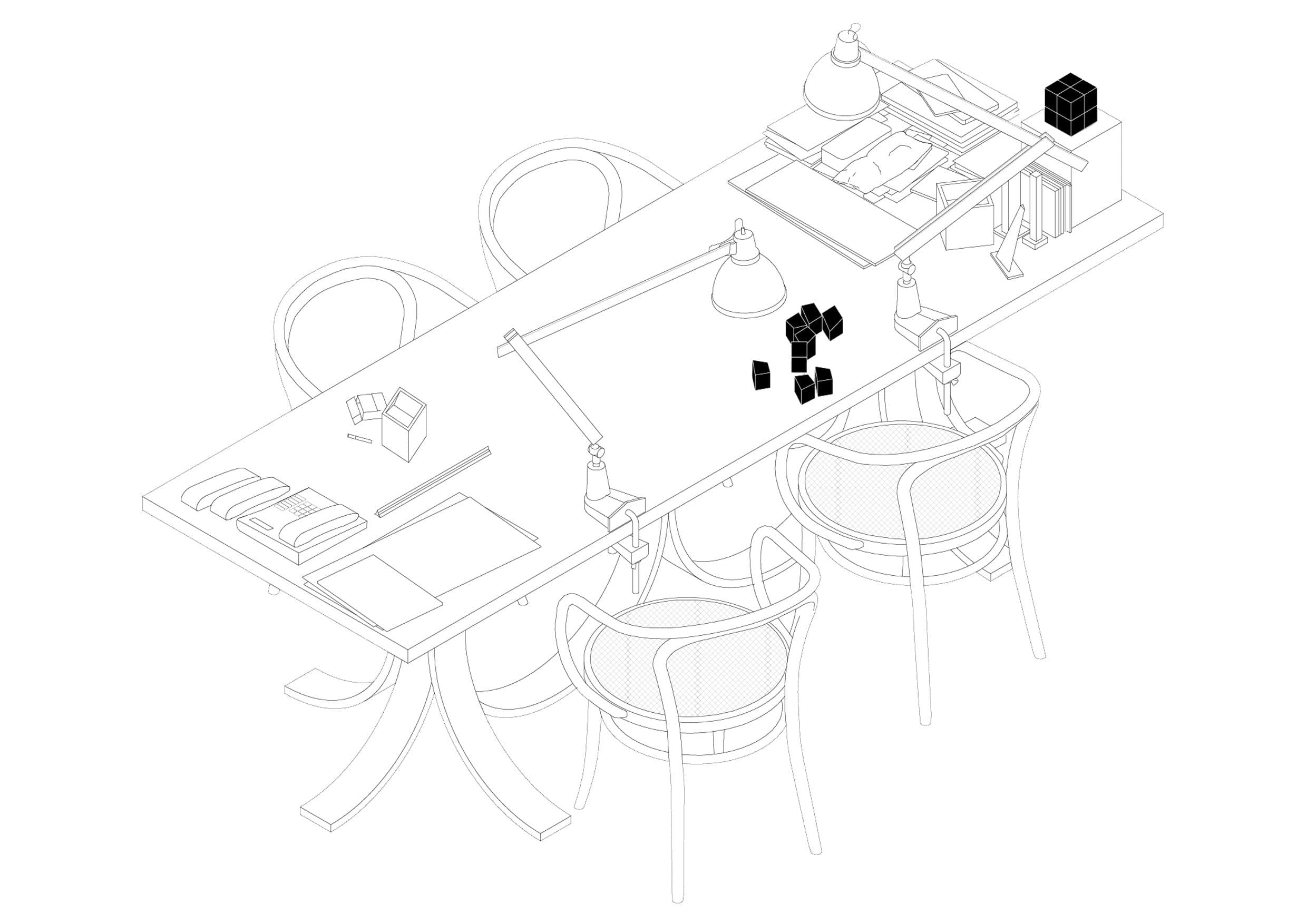

Many architectural careers are said to begin with a box. This mythological box is usually presented to an architect during her childhood. It contains an array of cubes, prisms, and -hedrons crafted from wood or plastic in various sizes and colours. At some point, these blocks are dumped from their container and onto the carpet, now ready to be transformed into whatever the child-architect imagines.

Assuming the child-architect has some level of tactile intelligence, she quickly learns that a stable structure begins with the largest blocks placed first. With a solid foundation in place, she then builds upwards, stacking progressively smaller blocks atop one another as the structure grows taller. (It always grows taller; the human instinct is to seek higher ground, to survey the surroundings for danger, water, food, or simply to manifest a desire for power or vanity, as some nascent form of compensation.)

Inevitably, with the slightest knock or breeze, the tower will teeter and topple, but this only begins the game all over again. The child-architect may tire and shift her focus to building outward instead – a castle, a farmyard, an entire village. If she grows bored of this too, the blocks will be set aside in favour of a ball, or a teddy, or an iPad, and packed back into the box for another day.

Decades later, the adult-architect may recall with some nostalgia the hours spent playing with these blocks. However romantic, her memory acknowledges an essential truth: the building block is the genesis of all architecture. The cube, as the simplest form of block, with its three orthogonal axes and six sides, represents the walls, floor, and ceiling of the traditional room, and did so long before the complexities of parametric modelling arrived.

Imagine a child asked to draw a house. The result will likely be a square with a triangle on top; a cube and a pyramid in three dimensions. Stretch that form along a horizontal axis, and the architect has a street; extend it vertically, and you have a skyscraper. By shifting, twisting, removing, and balancing these blocks, all sorts of possibilities come into play.

Cover photo by Jeroen Verrecht.