Form Follows Fantasy

Les Espaces d’Abraxas

LOCATION

Chicago

CLIENT

The Prime Group, Inc.

YEAR

1992

STATUS

Completed

BUA

110.000 SQM

Team Members

Ricardo Bofill Levi, Jean Pierre Carniaux, Rogelio Jiménez, Nabil Gholam, Rodrigo Bilbao, John Gleksak, Suzanne Strum, Kevin Bachelor, Alan Bombick, Lee Hamptian, Leo Modrcin

SEE CREDITS

OVERVIEW

LOCATION

Chicago

CLIENT

The Prime Group, Inc.

YEAR

1992

STATUS

Completed

BUA

110.000 SQM

In the field of architecture, few forms are as emblematic of American identity as the skyscraper. This is an invention born from the unique confluence of industrial ambition, rapid urbanisation, and an unyielding drive to build bigger, bolder, and more imposing symbols of economic power. Chicago is widely regarded as the birthplace of this architectural revolution, with the Home Insurance Building, completed in 1884, marking the first use of a steel frame.

As time has passed, America’s relentless quest to transcend the earthly limits of its cities has arguably come at the cost of design quality. The architectural traditions that shaped buildings for millennia have often been cast aside in the name of progress. In this light, 77 West Wacker Drive represents an effort to reconnect with some of these classical principles, reinterpreting them with contemporary construction techniques on a prime parcel of land beside the Chicago River.

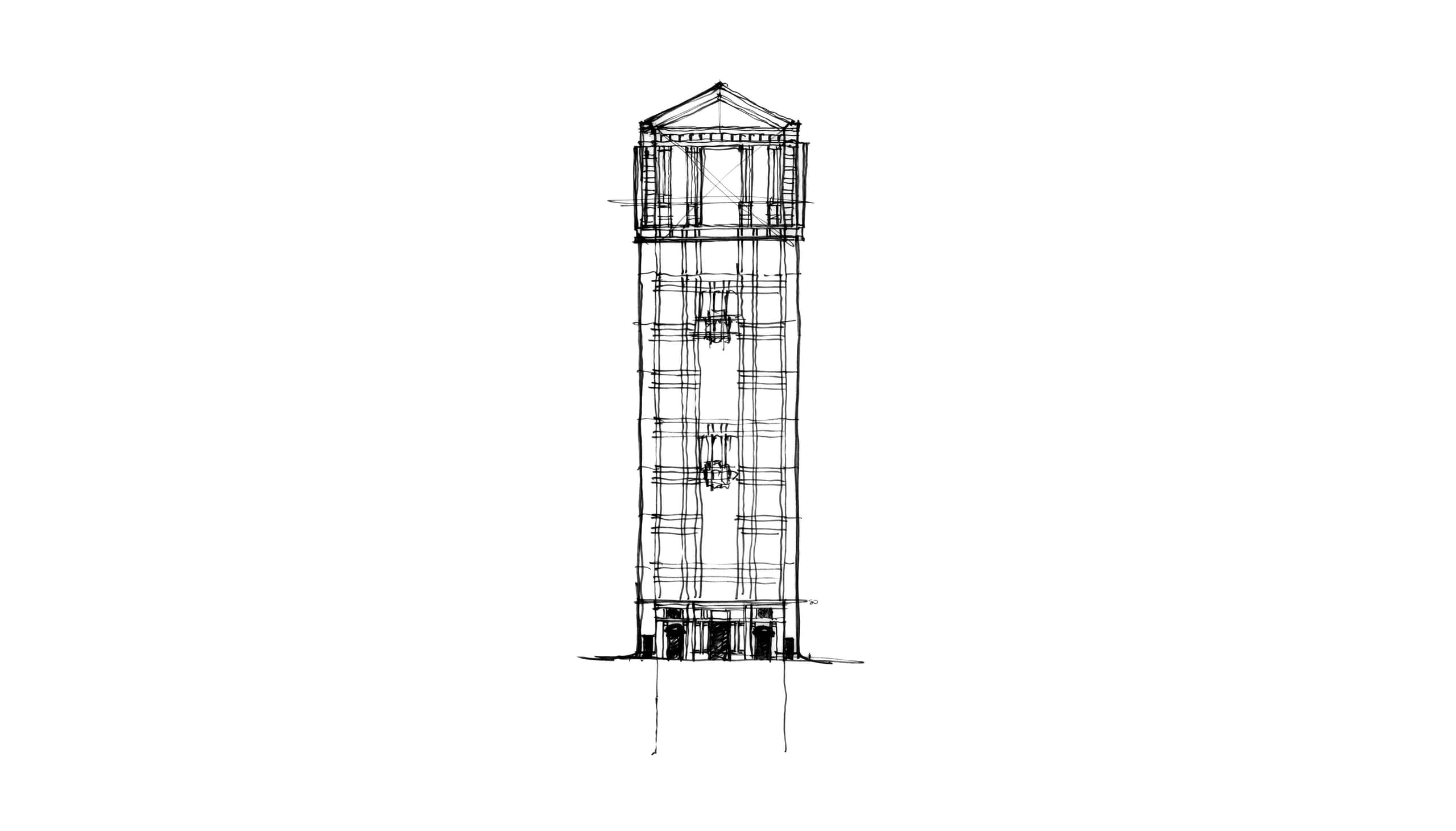

The 50-storey tower is composed of a base, shaft, and capital (much like the Greek orders), with proportions drawn from Giotto’s campanile at the Florence Cathedral. Its base is solid, built in Portuguese Royal white granite and designed with classical motifs to produce familiar, human-scale interactions with the building at street level. The shaft and pedimented capital of the tower receive a modern treatment, sheathed in a silver-grey curtain-wall system to allow for panoramic (and lucrative) views of the city.

As the last of the 80s-era speculative developments commissioned in Chicago, 77 West Wacker Drive reflects a transition in the way high-rise architecture is funded. Its core is designed with the economic realities of skyscraper construction in mind: optimised for space, it allows for maximum rentable area while still providing the architectural elegance characteristic of a significant urban structure.

The interiors feature elements such as coffered ceilings and pediments over doors, again drawing on classical architectural traditions (much like previous projects by the Taller, including Teatre Nacional de Catalunya and L'Arsenal de Metz). Special attention was paid to the detailing of the lobby, which is 18-metres tall and houses sculptures by Xavier Corberò, a mural by Antonio Tapies, a black-granite pond, as well as planted bamboo trees. Each of these details is part of a broader effort to infuse the building with classical grandeur, creating a timeless identity that will endure through the ages.

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA

GREGORI CIVERA

IMAGES BY

TALLER DE ARQUITECTURA

GREGORI CIVERA